I’ve been studying syndromic surveillance recently.

I studied this [0] document, which addresses shortcomings in syndromic surveillance. It may be rather outdated, but I feel that it raises a strong argument regarding what we’re doing wrong, and what needs to be improved.

Tradeoffs in many surveillance systems are

I’ve also considered,

Is it easier to work with more data, or less data? Can it be useful, or isn’t it worth the effort?

Another major objective in my mind-

You don’t need a system that will take up much resources, and finally say “ok, we calculate that you have an epidemic happening right here, right now”. Instead, we need something that says, “I’m detecting patterns which indicate a 50% chance of epidemic proportions in location A by next Monday. Based on these results, you need to keep an eye on Location B as well, since I’ve detected emerging patterns over there too.”

Syndromic surveillance tools should be able to identify any emerging illness pattern, not just biological attacks.

Ultimately, there is a limit to what an artificial system can do. I believe that the final decision regarding whether or not to issue an epidemic alert should lie with a medical practitioner. The surveillance systems’ purpose it to provide the practitioner with meaningful information that will help him take a decision. Nothing more, nothing less.

Decentralization

What are the tradeoffs between decentralizing and converging of syndromatic surveillance?

What’s the impact of considering data from a wide range of locations if we’re dealing with an epidemic that’s spread across a very small demographical region? Will this help us, or will it cause problems?

In my opinion, centralizing, or converging all health data into a single processing system encourages the possibility of a single point of failure.

On the other hand, de centralizing will improve the system by offering it not one, but several chances to succeed. It will also let us create a tool that will support both pandemic and epidemic surveillance.

Another point – check out this [1] an article on ‘Rapid detection of pandemic influenza in the presence of seasonal influenza’

My question is, how do we identify if it’s just a seasonal ‘spike’ or an emerging epidemic? And how do we map symptoms to specific illnesses, and make that match before it’s too late?

So how to detect an emerging outbreak?

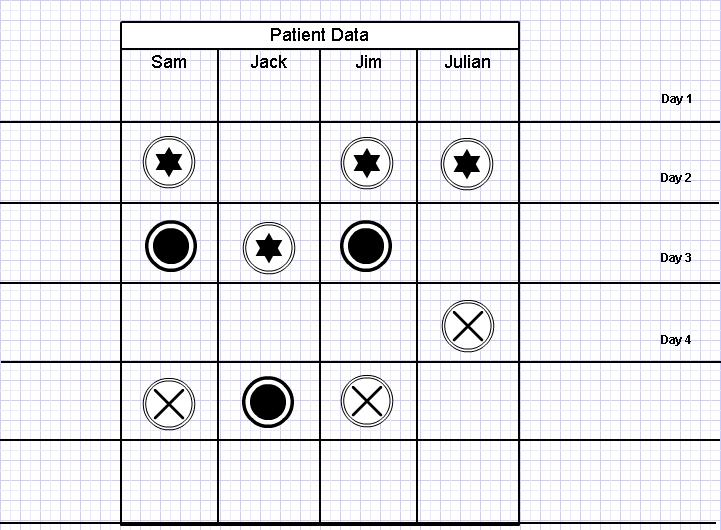

I came up with the following diagram to track patients and their symptoms for hospital A.

The three types of images given here depict different symptoms.

Assume the cases of Sam, Jack, Jim and Julian.

On Day 2, Sam, Jim and Julian all develop symptom A, which is associated with flu. So does this mean that we are facing an influenza epidemic? Maybe, maybe not. But on day three, Sam and Jim both develop symptom B. So now we have a pattern.

We also note that Sam and Jim go on to develop Symptom C on day 5. So this would definitely mean that Sam and Jim are suffering from the same illnesses.

But consider Jack. He developed symptom B a day later than normal. So what are his chances of suffering from the same illness as Sam and Jim?

And also, it seems that Julian has developed symptom A and C, but not B.

So based on this, and assuming that the symptoms are for flu, we could hypothetically come up with the following.

So now we have a pattern, and we can stay alert for it. This pattern can also be used together with mathematical disease modeling to watch for outbreaks at other locations as well. This works well with the centralized (converged) vs. decentralized surveillance model I described earlier.

For example, assuming we have five data sources (hospitals) and one central surveillance unit.

If the unit fails to identify an epidemic incident in source A, it will essentially fail to identify similar cases of epidemics in the remaining four sources as well.

But if de centralized, we are improving the chances of epidemic detection by five times.

Example: assuming that our system will detect an epidemic in source A, but fail to do so in other four sources.

Once the pandemic is identified in source A, the unit will extract a set of core ‘definers’ that will be sent to the other units for further processing. Each of the other centers will do a backwards check to see if there is an indication of such a pattern in symptoms reported to them. Not only do these centers get a second chance to check for mistakes, they also get a pre warning if an outbreak is imminent.

And assuming that a disease has only just infected the region, a different location may have only received reports of symptom A so far. If so, due to the indicators sent from other regions they will be able to make preparations for a possible outbreak depending on the emergence of symptom B as well.

We may even share the core definers with other hospitals to do a wider ranging check.

[0] http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9042/index1.html

[1] http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2458-10-726.pdf

I studied this [0] document, which addresses shortcomings in syndromic surveillance. It may be rather outdated, but I feel that it raises a strong argument regarding what we’re doing wrong, and what needs to be improved.

Tradeoffs in many surveillance systems are

- Sensitivity

- Timeliness

- False positive rates

I’ve also considered,

Is it easier to work with more data, or less data? Can it be useful, or isn’t it worth the effort?

Another major objective in my mind-

You don’t need a system that will take up much resources, and finally say “ok, we calculate that you have an epidemic happening right here, right now”. Instead, we need something that says, “I’m detecting patterns which indicate a 50% chance of epidemic proportions in location A by next Monday. Based on these results, you need to keep an eye on Location B as well, since I’ve detected emerging patterns over there too.”

Syndromic surveillance tools should be able to identify any emerging illness pattern, not just biological attacks.

Ultimately, there is a limit to what an artificial system can do. I believe that the final decision regarding whether or not to issue an epidemic alert should lie with a medical practitioner. The surveillance systems’ purpose it to provide the practitioner with meaningful information that will help him take a decision. Nothing more, nothing less.

Decentralization

What are the tradeoffs between decentralizing and converging of syndromatic surveillance?

What’s the impact of considering data from a wide range of locations if we’re dealing with an epidemic that’s spread across a very small demographical region? Will this help us, or will it cause problems?

In my opinion, centralizing, or converging all health data into a single processing system encourages the possibility of a single point of failure.

On the other hand, de centralizing will improve the system by offering it not one, but several chances to succeed. It will also let us create a tool that will support both pandemic and epidemic surveillance.

Another point – check out this [1] an article on ‘Rapid detection of pandemic influenza in the presence of seasonal influenza’

My question is, how do we identify if it’s just a seasonal ‘spike’ or an emerging epidemic? And how do we map symptoms to specific illnesses, and make that match before it’s too late?

So how to detect an emerging outbreak?

I came up with the following diagram to track patients and their symptoms for hospital A.

The three types of images given here depict different symptoms.

Assume the cases of Sam, Jack, Jim and Julian.

On Day 2, Sam, Jim and Julian all develop symptom A, which is associated with flu. So does this mean that we are facing an influenza epidemic? Maybe, maybe not. But on day three, Sam and Jim both develop symptom B. So now we have a pattern.

We also note that Sam and Jim go on to develop Symptom C on day 5. So this would definitely mean that Sam and Jim are suffering from the same illnesses.

But consider Jack. He developed symptom B a day later than normal. So what are his chances of suffering from the same illness as Sam and Jim?

And also, it seems that Julian has developed symptom A and C, but not B.

So based on this, and assuming that the symptoms are for flu, we could hypothetically come up with the following.

- Julian is suffering from ordinary flu

- Sam and Jim are suffering from Influenza.

- Jack is possibly suffering from Influenza.

So now we have a pattern, and we can stay alert for it. This pattern can also be used together with mathematical disease modeling to watch for outbreaks at other locations as well. This works well with the centralized (converged) vs. decentralized surveillance model I described earlier.

For example, assuming we have five data sources (hospitals) and one central surveillance unit.

If the unit fails to identify an epidemic incident in source A, it will essentially fail to identify similar cases of epidemics in the remaining four sources as well.

But if de centralized, we are improving the chances of epidemic detection by five times.

Example: assuming that our system will detect an epidemic in source A, but fail to do so in other four sources.

Once the pandemic is identified in source A, the unit will extract a set of core ‘definers’ that will be sent to the other units for further processing. Each of the other centers will do a backwards check to see if there is an indication of such a pattern in symptoms reported to them. Not only do these centers get a second chance to check for mistakes, they also get a pre warning if an outbreak is imminent.

And assuming that a disease has only just infected the region, a different location may have only received reports of symptom A so far. If so, due to the indicators sent from other regions they will be able to make preparations for a possible outbreak depending on the emergence of symptom B as well.

We may even share the core definers with other hospitals to do a wider ranging check.

[0] http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9042/index1.html

[1] http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2458-10-726.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment